‘March 19th, 1850.

‘Dear Ellen,—I have got home again, and now that the visit is over, I am, as usual, glad I have been; not that I could have endured to prolong it: a few days at once, in an utterly strange place, amongst utterly strange faces, is quite enough for me.

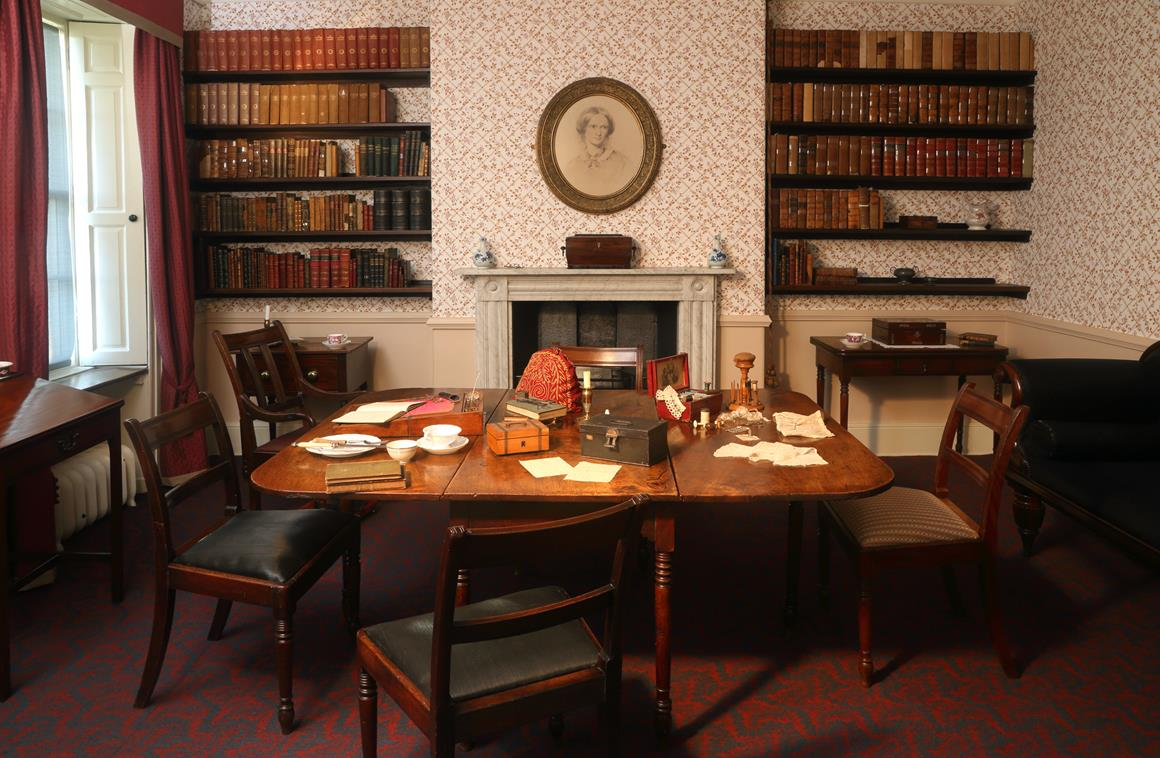

‘When the train stopped at Burnley, I found Sir James waiting for me. A drive of about three miles brought us to the gates of Gawthorpe, and after passing up a somewhat desolate avenue, there towered the hall—grey, antique, castellated, and stately—before me. It is 250 years old, and, within as without, is a model of old English architecture. The arms and the strange crest of the Shuttleworths are carved on the oak pannelling of each room. They are not a parvenue family, but date from the days of Richard III. This part of Lancashire seems rather remarkable for its houses of ancient race. The Townleys, who live near, go back to the Conquest.

‘The people, however, were of still more interest to me than the house. Lady Shuttleworth is a little woman, thirty-two years old, with a pretty, smooth, lively face. Of pretension to aristocratic airs she may be entirely acquitted; of frankness, good-humour, and activity she has enough; truth obliges me to add, that, as it seems to me, grace, dignity, fine feeling were p. 449not in the inventory of her qualities. These last are precisely what her husband possesses. In manner he can be gracious and dignified; his tastes and feelings are capable of elevation; frank he is not, but, on the contrary, politic; he calls himself a man of the world and knows the world’s ways; courtly and affable in some points of view, he is strict and rigorous in others. In him high mental cultivation is combined with an extended range of observation, and thoroughly practical views and habits. His nerves are naturally acutely sensitive, and the present very critical state of his health has exaggerated sensitiveness into irritability. His wife is of a temperament precisely suited to nurse him and wait on him; if her sensations were more delicate and acute she would not do half so well. They get on perfectly together. The children—there are four of them—are all fine children in their way.

They have a young German lady as governess—a quiet, well-instructed, interesting girl, whom I took to at once, and, in my heart, liked better than anything else in the house. She also instinctively took to me. She is very well treated for a governess, but wore the usual pale, despondent look of her class. She told me she was home-sick, and she looked so.

‘I have received the parcel containing the cushion and all the etcetera, for which I thank you very much. I suppose I must begin with the group of flowers; I don’t know how I shall manage it, but I shall try. I have a good number of letters to answer—from Mr. Smith, from Mr. Williams, from Thornton Hunt, Lætitia Wheelwright, Harriet Dyson—and so I must bid you good-bye for the present.

p. 449

Write to me soon. The brief absence from home, though in some respects trying and painful in itself, has, I think, given me a little better tone of spirit. All through this month of February I have had a crushing time of it. I could not escape from or rise above certain most mournful recollections—the last few days, the sufferings, the remembered words, most sorrowful to me, of those who, Faith assures me, are now happy. At evening and bed-time such thoughts would haunt me, bringing a weary heartache. Good-bye, dear Nell.—Yours faithfully, ‘C. B.’

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten